Convicts offered as workers in commercial abattoirs

Toronto Star, 27 April 1974, Jim Robinson [click to view original article]

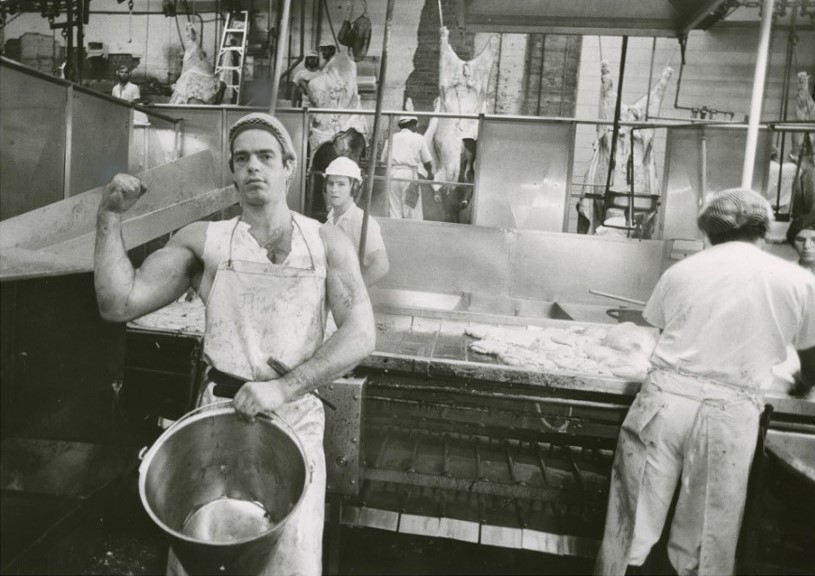

In the abattoir at Guelph Correctional Centre inmates and civilians work at the cutting table preparing meat for correctional institutions and mental hospitals. They’re being offered to private industry at regular salaries. Photo credit Dick Darrell 1974.

You’ve got to admit it sounds bizarre.

Fifty inmates – or more – at Guelph Correctional Centre are being offered to private industry as slaughterhouse workers. Their job will be to kill thousands of animals in the centre’s own abattoir, cut them into pieces and pack them for public sale under some company’s brand name.

They’ll be paid the going wage.

If the thought of a room filled with knife-wielding, meat-cutting convicts makes you uneasy, that feeling is just one hurdle the province’s new prison industrial program must clear.

Will rival slaughterhouses object to a competitor using convict labor? Will packing-house unions oppose such work? Will taxpayers object to inmates earning more money than they themselves may earn? A lot of questions remain unanswered.

This week I went to Guelph to get some answers. I visited the brooding, 63-year-old stone-and-brick cellblocks. I toured the kill room and the cutting rooms of its modern abattoir. And I talked with inmates like the tousle-haired youth named Reefer.

“It would make a lot of difference,” he says.

Inmates like Reefer now earn up to $5 a week in Ontario’s institutions – under an allowance system based on total behavior. In the new program they can make $2 to $4 an hour as relatively inexperienced slaughterhouse workers.

Learn to cope

The idea, says government information officer Don Kerr, is that a job with worthwhile pay may teach convicts to cope with a regular working lifestyle so they’ll be able to survive on the outside.

“It’s not as if he’s never going to get out,” says Kerr, who worries about people who think a prisoner should be punished.

“Look out, lady,” he warns. “Because if he can’t function when he eventually gets out, he’s going to be a repeater.”

The Ministry of Correctional Services frankly admits that a major problem in training inmates has been in motivating them to want to work. Forcing them may get a job done – reluctantly – but it does little to develop pro-work attitudes, it says.

The 15 to 30 Guelph inmates who now work in the abattoir preparing meat for the province’s correctional institutions and mental hospitals get two rewards – their $5 a week and a way to pass the time.

“Both of those rewards aren’t sufficient for our clientele – as they aren’t for most of us,” says assistant deputy minister G. R. Thompson.

The strange choice of a slaughterhouse as a project pilot was largely pragmatic. When Premier William Davis announced the prison industrial program in his Throne Speech last month, he avoided mentioning the kind of work involved.

“We happen to have the abattoir there,” says John Pahapill, the self-confident 46-year-old mechanical engineer hired in February to head the project.

“It’s a relatively large investment and it’s relatively well-equipped compared to some of the other industrial facilities we have. And it is very, very under-utilized. It is producing a product that is very much in demand in Canada and there is an acute shortage of experienced workers in the industry.”

The ministry has advertised its plan to about 30 meat processors in the province who are licenced by the federal Department of Agriculture, says Pahapill. A formal call for tenders is being prepared.

“The industry would provide supervision and management and on-the-job training,” he says. “We, of course, would provide careful pre-screening of inmates.”

“There is a bit of risk involved, of course,” Pahapill conceded.

“The inmates will have to be very, very carefully picked.”

A University of Toronto graduate, Pahapill was manufacturing manager for KeepRite Products Ltd., makers of industrial heat transfer equipment in London, Ont., when he was hired to head the new prison industry program.

Before that he spent about 14 years with American Standard, the giant U.S.-based plumbing and heating firm, where he worked his way up to general manager of their industrial equipment plant at Bramalea. He says he left because the company was planning to move part of its operations to the U.S.

His only experience in a correctional institution was in 1945 when he spent a night in a Swedish half-way house while travelling with his family, refugees from Estonia.

“The opportunity that has always been on my mind is community service for government,” he says as we turn up Highway 6 to Guelph.

“This one happened to come along. I read it in the newspapers. I applied last December and I had some pretty serious discussions. They explained their program to me and I thought ‘This is it.’”

All sorts of details still have to be worked out. Will inmates pay into the Unemployment Insurance Plan? The Canada Pension Plan? How do labor laws apply? What if a union wants to organize them?

“At Guelph the inmates are very favorable,” says Pahapill. “Our problem is to make sure that we don’t give them any false hopes.”

Pahapill admits that the higher wages may not motivate the convicts.

We turn into the centre’s grounds through an estate-like entrance and drive up a long driveway flanked by manicured lawns, evergreens and a stone fence that snakes beside the road.

The abattoir is a two-storey red brick building to the rear of the grounds, behind the cellblocks and the fruit and vegetable cannery. It was built in 1967. It looks surprisingly small.

Some physical changes will be required to convert it to a commercial operation, says Pahapill.

Cutting day

“Our conveyor system in the kill room is a gravity feed system, which restricts us to a one-at-a-time basis,” he says. The federal Department of Agriculture will require that the side-by-side kill boxes for beef and hogs be separated. Cooling rooms will have to be enlarged. The processing equipment for inedible parts will be removed.

Foreman Joe Ellis hands us white smocks and tells us that today is a cutting day – not a kill day. We won’t see any slaughtering.

There are 63 hogs lying silent in a single pen near the loading dock. They’ll be butchered the next day, says Ellis. As we enter, the hogs jump to their feet and push nervously against each other, churning up the straw and wood chips on the floor. But their squealing quickly dies down.

The pen is one of many in the long waiting room. All the others are empty. Ellis says it’s an average herd for the once-a-week Tuesday hog killing. About 25 cattle will come in on Tuesday morning and another 30 to 35 will be butchered on Wednesday.

We pass the narrow, steep-sided steel runways through which the animals will be driven one at a time to the polished steel kill box. A hog stands in it with its feet close together while a two-pronged “electric torch” is held to its head, sending 400 volts through its brain.

Then the stunned hog is hoisted on a chain with a hook. An electrically-driven overhead conveyor takes it to the blood bay where, still hanging, its throat is cut with a knife.

Boiling water

After it has bled, it goes into a scalder where boiling water cleans the carcass.

Superintendent Scott Keane, who took charge of the Guelph centre 18 months ago, tells us later he doesn’t like visiting the abattoir. He says he thinks he has heard the hogs still making sounds when they go into the scalder.

Cattle are killed differently, Ellis says. They’re stunned by firing a bolt four inches long and three-eighths of an inch thick into their heads. Then they’re conveyed to the blood bay and their heads are removed with an electric saw.

We follow the process in the silent, spotlessly clean, steel and concrete room – a maze of conveyors, pipes, hooks and saw blades.

We pass through a holding cooler, half filled with dozens and dozens of beef sides hanging heavily in rows from those mean-looking hooks we’ve all seen in movies.

Ellis says some inmates who work in the abattoir have volunteered for the job but others have been sent there. He swings open a vault-like door and we enter a cutting room filled with people.

An inmate at Guelph Correctional Centre shows off the strength he uses to pry apart jaws of steer skulls at work at Better Beef Ltd., a private packing firm operating on the grounds of the reformatory. Photo credit Pat Brennan 1982.

It’s not a very big room and seems cramped. More than half the men bent over the cutting tables are wearing white construction hats, which means they’re civilians from outside. In the far half of the room are a dozen yellow-hatted inmates.

“I’ve been around here 17 years and I’ve never been threatened with a knife or anything,” says Ellis as we pass among them. I ask about the hair nets under the inmates’ hats and he says they’re required by law.

“They won’t make them cut their hair,” Ellis says. “The day they took the old strap away was the day we lost control of them.”

Around us, young men in hats of both colors are slicing up steaks, sawing roasts, bagging hamburger and stacking cardboard boxes destined for 54 institutions across the province.

One of the stackers has the name Reefer penned across his yellow hat. I ask him what he thinks of the plan to pay wages for the work he’s doing.

Learn trade

“This is a good job here if guys want to work it,” says Reefer, who says he’s 20 years old, comes from Hamilton and is serving seven months for breaking and entering, and car theft. He’ll be out in May.

“I’ve worked down here for four months,” he says. “A guy getting paid – at least when he walks out of here he doesn’t have to go on welfare. He’s got himself a trade.

“Some guys have got a wife and kids outside and it (regular wages) would be great for them. That way they wouldn’t be on welfare and the taxpayer would save some money. And the guy’d be doing something.”

Another 20-year-old inmate, from Niagara Falls, says most inmates favor the new system – “at least the ones in here.”

“It’s a job, right?” he says of the slaughterhouse. “I mean a trade, sort of. I like it.”

“But personally,” he confides, “on the kill floor – some jobs in there I don’t like too much.”

Back in Ellis’ office, Ellis explains some of his doubts for the private industry program. He says there’s a tremendous staffing problem.

“We can’t depend on the inmates. They stall or they’re on sick parade or they have visitors or they want to see a psychiatrist or somebody.”

Some days 30 inmates start work, but by the end of the day only 15 remain, he says.

Inmates may start at $2 or $2.50 an hour and be paid more according to their output, he says.

Ellis says some civilians in the textile mill in town are making less than that after years of work.

As we drive away, Pahapill concedes there’ll be problems with the attitude of some of the staff over the prison industry program. One reason the abattoir was picked was because Scott Keane is there, he says.

“At this institution we have a superintendent who is not opposed to new ideas.”

Next stage

The province is already making plans for the next stage in the program – a 30,000-square-foot industrial facility at its new 200-bed Maplehurst Correctional Centre at Milton, scheduled to open in mid-1975.

The government will be inviting offers from private industry to use the plant for light manufacturing, says Pahapill. He’ll be looking for labor-intensive jobs, such as product assembly, which are relatively easy to learn.

There will be obstacles – some anticipated, some not. But there’s a lot of confidence in Pahapill’s solid face.

“I’ve always been a bit of a bulldozer,” he says.